Writing Without Looking

There Are No Shortcuts

Where writing is concerned, we can easily spend years discussing specific situations, how they might be introduced and managed, the importance they bear regarding a larger narrative, mistakes made, poor judgment, assumptions, writing strategies... and so on. The number of directions we might take in introducing two characters to each other would allow us to write not one article on their meeting, not two, but really as many as we might choose to write. Writing is fractal. Any narrative moment can be woven into a world of intention, technique and consequence. Writing itself is a dynamic and inexhaustible field... limited only by our willingness to look the beast in the eye before flinching.

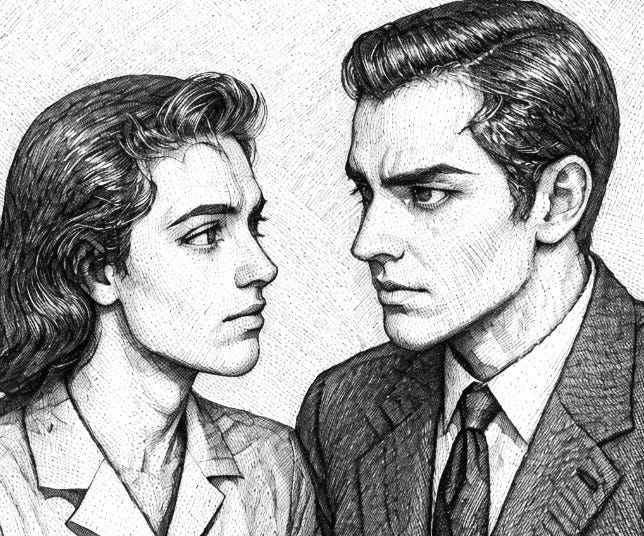

Let us assume that we've chosen to introduce two characters to one another as a love interest — which I choose specifically because while the film rom-com genre is in its death throes, erotic fiction is surging. It really doesn't matter what traditional writing trope we might begin with: the introduction of an expert, such as the "detective"; the death of a character; the spiral into disconsolation at the end of a romance. Yet I'm going to choose this, because in the previous essay, we brought it up as one way we might start a novel.

In giving advice on writing, I prefer to build rather than tear down. I feel it's best, if the characters are going to embark upon a romantic journey, that they're introduced to the readers together; that the readers meet both characters at the same time as the characters meet each other. It's a common technique now to give each character a chapter, then to bring the characters together in chapter three, or even later — but apart from the benefit where page count is concerned, I don't see this as desirable for the reader at all. Meeting one character, particularly one engaged in lengthy self-reflection, for a whole chapter, is a recipe for sterility. Doing it again, a second time, and right after the first, feels to me like the unpleasant orientation one faces on our first day at work — only to be told that because the boss wasn't there, we must go through it all again on the second day. I prefer to start a job by starting it. If safety is concerned, an orientation is necessary. A book is completely safe without one.

We're often encouraged to open a scene with some kind of tension. The cliche of an individual running in terror, in a dark, desolate place, looking back while stumbling, has long featured at a story's start. Having seen it so often, we expect something to come out of the dark; we expect the character to die, or perhaps be merely attacked — taking us to the next scene at a hospital, while a concerned detective bends over the body in puzzlement. This, we are told, is how to grab the reader's attention. Introduce something momentous, something fast paced, something terrifying... something that starts with a bang.

Yet we are not writing to an audience opening pulp dime-novels in the 1930s, when this advice was pounded on desks manned by grisly editors shouting for crime, blood, lust, fear — we have had a hundred years of this and there are none of us not jaded. Those stories that still hinge on this content, for there shall always be such stories, prey on the uninitiated young, while their minds are still fresh and their eyes still able to widen in shock, or those with a peculiar taste for gore, for whom it is no longer the shock but the aesthetic. For the rest of us, this alone won't do the job. Like well-travelled carnival-goers, we've seen the "alligator" boy, the woman who turns into a gorilla and the chicken that can add 24 and 17. These things seem a little sad now; we have greater concern for who is being exploited than we have for our voyeurism. We want more than "thrills." They're not thrilling anymore.

Eventually, every experienced writer comes to understand that it's not the event that puts 'em in the seats, it's the writing itself. Bold, insightful, spellbinding writing is what grabs them. A solid, well-paced, intuitive moment of two people thrust into a situation where their dialogue, their word choice, their peculiarities, their ability to be both like the reader and completely unlike the reader is what drives the book from the first page to the tenth, as the reader quickly discovers not only do they like the one, they like the other too. The phrasing is snappy, the characters brazen, cheeky and unshrinking — and the moment so richly believable that it feels that something like it might happen to us one day. This, not people running in the dark, is what sells a lot of books.

How is it done?

That is the question, is it not? It's easy enough to say, "do this," but if there's no frame in our thoughts for how "this" is done, we might just as well write pulp. At least that has a clear, evident template that works in plug-and-play style, while there are loads of young teens without bills to pay, with wads of cash they don't know how to spend. Still, there's quite a lot of competition; while at the same time, churning out ten or twelve books of this really starts to feel like having a real job... not one as cool as being a "writer."

The perpetual elephant in the room, the little side-step we see creative writing instructors do, is the unpleasant reality of needing to get past 350,000 words that need picking over, an excess of possibility, the fertile imagination we want but haven't got... and all that work that needs doing. If only none of this were necessary. If only there were a short cut. This is what I hear and see when I search for "how to write" content. We're told, it isn't necessary. We're told, use this short cut. By those whose names we don't know, who have written "highly successful books" we've never heard of, advertised on sites without numbers. With two brief reviews on Amazon.

I don't have a shortcut, but I do have a guaranteed, one-hundred-percent successful plan if you want to write with the profundity and skill of anyone, even Shakespeare. Here's how. Get up tomorrow and read an entire Shakespeare play, start-to-finish. Then, with whatever part of the day that's left, type lines from the play, from the very start, into the internet and have any of the hundreds of concordances that exist for free explain the line to you. Then the day after, get up, read another complete play; doesn't matter which, for this, they're all equally fine. Then continue examining the first play, or the second, line for line, until it's time to go to bed. Then on the third day, pick another play by Shakespeare and... well we can see where it goes. When all the plays have been read, read them again. And again. And again. And keep researching the lines. Memorise the plays. Repeat them to yourself all the time. Start playing with the lines, moving them around... and when you feel ready, start trying to construct your own play. Keep reading the plays you have, probably skimming them now, but get what you can out of them. Keep researching the lines. Don't stop. After five or six years of that, you'll be ready to stage your first play.

But I'm betting you'll probably have quit before then. Because, in reality, it's likely you don't like Shakespeare all that much. Even if you thought you did.

Truth is, to write the scene between the two characters who fall in love with sufficient aplomb, it has to be done with genius gleaned through an appetite for work. Those who achieve the level of skill necessary to choose a scene, any scene, and infuse it with the intensity it wants, do so because from the beginning, all they ever wanted to do was write. They did not care about any specific reader, or appealing to a number of readers. They cared about a story in their head that they wanted to tell with grace, confidence and self-service. When they reached a point where they could not improve that story, they started another one. And another, and another. Until the day comes that whatever they want to turn their hand to, it just seems to work. At which point, it's hard to say why, even for them.

Writers, at some point, move past attending to the words. This is difficult to understand, but it is so. The message is the key; we cease to look for words with our thoughts; we're too busy being concerned with what Sam wants, with what Dave wants, with how they comprehend each other, with how we want to essay that comprehension, line-by-line. The words themselves simply cease being there.

I shall try a metaphor. I used to cook professionally. This is done on a "line," where food is stored in rows and rows of containers, from which different foods are collected and assembled together into three- or four-score menu items. Much of the time, this work is done at speed, which is to say very quickly, staggeringly quickly for some who haven't done it for years. Assembling a pizza, say, when every pizza combination differs, is a matter of reaching into a vessel and extracting cheese, pepperoni, ham, black olives, green peppers... all while also making three steaks, two saucepans with pasta, a basket of fries and another basket with chicken tenders, while two pizzas without timers are cooking in the adjacent oven. What would be, given my experience, an ordinary, not-at-all challenging scenario.

We do not look at the container where the pepperoni is, or where the green peppers are. The eye isn't necessary. The hand has reached for the ham and the cheese so often that it blindly reaches and there are the olives to be clutched and tossed evenly over the pizza, which we do not look down at. We chat about last night's hockey game or who the server is dating now as the cheese is spread over the top, done unconsciously, for most things are done unconsciously once they are done often enough.

This is writing, eventually. It does not matter any more how the meeting is written; it matters what happens at the meeting. The words, when needed, like the green peppers, arrive, fitting perfectly, slid into the oven and browned, while the story unfolds line by line without the hesitation of writers who are unsure if this is the right adjective or if that sentence is too complex. Sam thinks Dave is cute; Dave is surprised by Sam's ability to apprehend what he's saying, where most don't. He thinks of asking her for coffee; she hopes he will, then is frustrated when he doesn't; she drops a hint about how she should call her mother, but there's no hurry. He misses the hint; she invites him; he agrees, suggests a place he really likes and they start walking there.

There are no words. There are ideas, intentions, playful banter between the actors, a dropped hint about Sam's need for self-sufficiency, a gentle reference to Dave's willingness to surrender it... those momentary clues to the day when Sam wants to leave her job because it wants her to sacrifice her autonomy for the sake of duty, which she doesn't understand but he does, so that he can explain it then in a way that she can understand. That work can be done now, but in oh such a subtle way... but we don't do it with words, we do it through understanding the direction and theme of everything we mean to write, between here and then, though we may not get to "then" for months or even years. Depending.

If this isn't clear, then it's because not enough writing has been done. Write more. Write often. Measure the words as less important than the purpose. Try to enjoy it. And don't get distracted by success. Success always comes to those who wait.