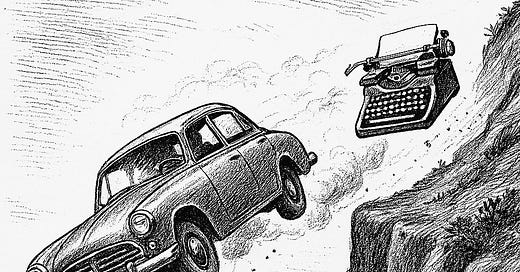

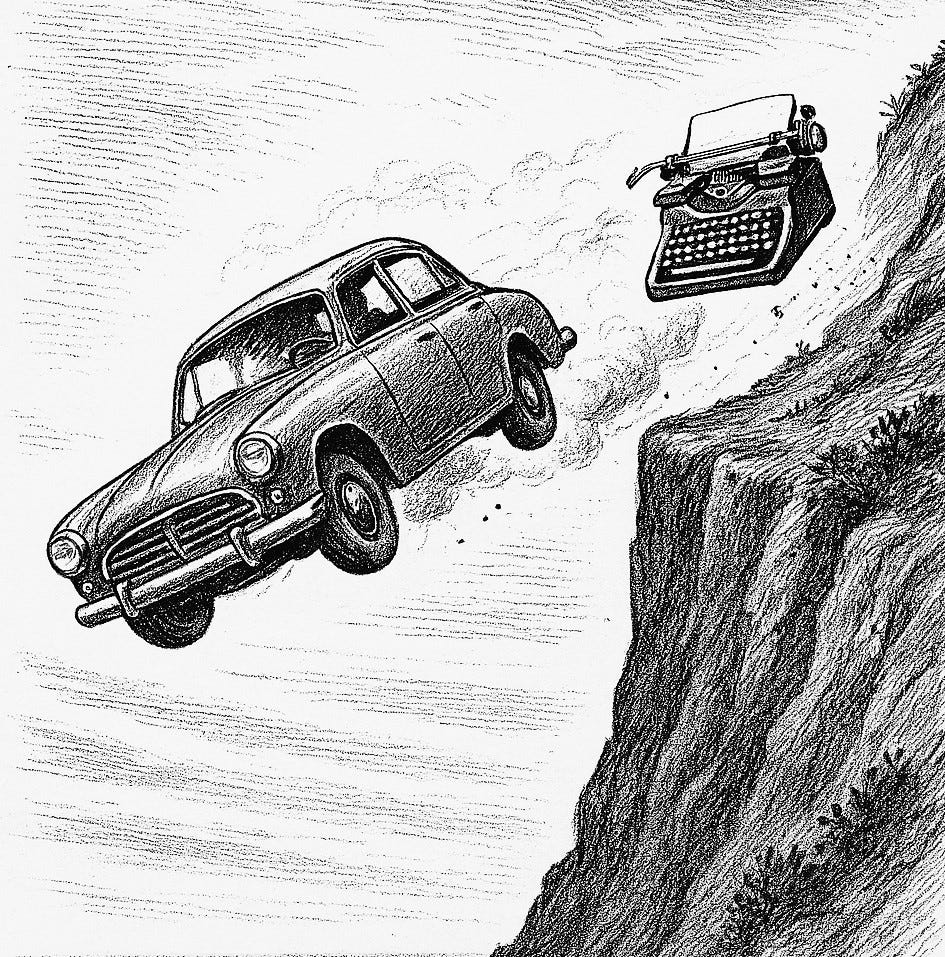

For shorthand, let's call the moment, "car-off-a-cliff"... the split-second, disastrous consequence when every plan, every hope, every possible reward, is now plummeting to an irretrievable death. Writers dream of such moments, for it gives us a chance to turn a story on its head, to surprise and shock the reader — and to invest the remaining characters with an opportunity to be devastated, resilient — all those great things that seem to make a story meaningful. But while the moment is a great twist... is it a good idea?

Many include such things in their books for the sake of spectacle. We're encouraged to do it; sometimes we're shamed if we don't do it. But there are consequences to such plot points that many don't consider. To begin with, much of the momentum, character and anticipation is cut off, like a light switch... though it's of necessity that we make everything up to the point before the cliff as real and believable as possible. Readers invested in the plans we've laid out, who want to know the success of those plans, will feel cheated when all that is ripped to tatters by a cheap, perhaps gratuitous-looking plot device. Up until then, if the readers are with us, they've listened to the hopes and expectations of our former, now-dead characters... and as a reward for that, we've swooped in, slapped them across the face and killed the likeable characters we've built for what might reasonably be seen as no good reason. Think of the scenes now made redundant by the car's flight. Consider how they'll look to a reader wanting to read the story again — how hollowed-out, since it all comes to naught. In some cases, scenes will look deliberately designed to pull the reader's chain; in others, that the scene need not have been written at all.

When promises are made by a narrative, we are bound to keep them; we risk not only the reader's reaction of throwing the book across the room, but the real danger that they'll remember our names and never read a book from us again. These consequences, however, are often downplayed or overlooked in our quest for dramatic impacts and commercial expectations. Yet it's not the publisher that pays the price. It's us.

There is another consequence. Knowing that there's a spectacular fireball coming, a writer may feel inclined to rush through the presentation of those characters and their nuanced goals. After all, the writer knows they're going to die on page 251; it's natural to focus on those who are going to live, to focus on their story as the ones that actually matter. Without much investment paid to those slated to die, the crash really hasn't much impact. Without really investing in those characters, the twist won't be one. It might, even, be predictable. If the reader doesn't really care about Gerrit's hope to start a restaurant, or if Natalie ever will work things out with Shayne, then who really cares if they die? If they're not installed with every ounce of flesh and nuance-enriched verve that we can muster, the reader may bow out before the car's squealing wheels leave rubber into nowhere. For those who get there, instead of a jarring twist, the event reads like a check box.

This gives us an unwelcome Catch-22. We must either invest our all in characters who are going to die — and be burned in effigy for doing so — or we might fail to invest and find ourselves at the side of a road holding up a sign that reads, "Please finish my book." Where's the win here? Can it be done?

Yes, but it's tricky. Essentially, it requires writing two books, one intertwined within the other. In the first book, we write not only the obstacles and triumphs of those who must pay the price for the sake of narrative, but also invest their actions with a different payoff that can't arrive in the story until after they're dead. Meanwhile, in the second book, we set up characters, Tonya and Shayne, whose character arcs necessarily revolve around the doomed characters, while carefully granting them the potential to break free and succeed on their own. Then, when Natalie and Gerrit die, Tonya and Shayne — for a moment — seem helpless, only to be cleverly redeemed. Tonya, her hopes of working alongside Gerrit, because she never had the nerve to start her own restaurant, discovers Gerrit's 17-step-guide to redemption. We watch as this walks her through the hardest parts, as we see her character resolve, until she opens Gerrit's restaurant, with the appropriate name. Meanwhile, Shayne, bereft of Natalie, is now thrust into a place where their son's future now depends on him; all this time, he hasn't been a very good Dad, he's always let Natalie handle it. But now we see him step up, we see him make the connection... we see him become the father Natalie wanted him to be.

By taking this approach, we invest a resonance that lingers beyond the deaths of those who, up until page 251, seemed like the main characters. By seeding redemptive payoff into the arcs of those who survive, we create a kind of narrative echo. This echo is the second book: Tonya and Shayne's story, not just reacting to tragedy, but rising above it. In this manner, the car-off-the-cliff moment doesn't flatten the narrative, because Natalie and Gerrit don't really die. The accident catalyses what comes after. It allows for devastation and continuation. It's grief with purpose, shock with structure. It's how we avoid the cheap route, insisting that the story, even at its darkest, must mean something.

It takes a first-class writer to foresee and construct on this level. Without patience, skill, the ability to carefully lay the foundation without making it obvious, the payoff can easily look contrived and unearned. Slapped on, so to speak, so that the reader doesn't see it as Shayne becoming a father, but as Shayne's character "conveniently" acting not like Shayne. That potential father has to be there in the first chapter; it has to lay a foundation for every argument Natalie and Shayne have about it. Every conversation between the four characters must do triple duty: moving the plot, deepening relationships and seeding transformation, on every page before the wreck.

This is why this article isn't to teach how this is done. Those who can, who have earned their stripes, don't need me to explain it. This article is for the rest, who want the showiness for the glitz and glamour, who just want to see things blow up. For those who are with me now, don't write this. Write commonplace, everyday scenes that build stories that don't cheat the reader, that don't break contracts. It's hard enough to make a story stand on its own hind feet without the jazz hands. Concentrate, first, on finishing stories. Learn how to write them well enough that readers won't put them down, despite their lacking a car-off-a-cliff. The drama we want to depict, first, is the real thing: human tension, emotional consequence, earned stakes. We need to excel at this, before we excel at that.

Yet we'd be remiss if we didn't take a little time to address these themes. To do so, we must compare them with 'escapism.' I wish to go on record saying that escapism is fine. We should all play in fields of sci-fi fantasy murder-mystery erotica, because it's fun. Yet we must acknowledge that escapism is more precisely a search for comfort, distraction and relief from the challenges or difficulty of everyday life. It exists for the purpose of side-stepping real world problems... and the further from those problems that it gets, the deeper and richer and more ridiculously distant a place it inhabits from the unpleasantness of bills, workplaces and unrelenting parenthood, the better. The measure of quality is therefore commensurately lower — or, perhaps, just different. We engage in the logic of a magic system, in the complexity of family trees associated with multiple royal houses, in the biology of impossible creatures like dragons and balrogs. The answers to these questions within the works can be certified and granted immunity from inquiry by the writer's ability to sound real... in a universe where no physical laws nor inflexible consequences exist. This all makes escapism a wonderful sandbox.

But when the book is put down, the sandbox evaporates... and what's left is all this inescapable unpleasantness. We have to get out of the car now and walk into our place of work. A diaper needs changing. The dishes wait. We haven't the money for our car insurance. It's all awful, but it's real.

At some point we must consider work that does more than escape from this world, but rather acts like a guide through it. That reminds us of those things we don't dislike about life; of the reasons why we submit ourselves to diapers, why the dishes offer opportunities for joining together and talking each evening. Why the car insurance is overcome through friends, family, negotiation and a realistic, hard-worn skill at navigating our world.

The story-beats I ascribed above to "patience" and "foresight" is the way we address the vulgarity of grief, guilt, fear, love and regret... all the things we can't escape from. Guilt in a sci-fi novel never has the same weight, because it's for taking actions we're never going to take in real life. The grief a princess feels at the loss of a prince cannot equivocate to the parent's loss of a child, or the inevitable separation of a couple that have been together 50 years. We depict love, fear and regret in escapist works — but these things are never as muddy or as uncertain as they really are; in effect, we look at them with a detached, through a mirror perspective, shrunk down to where we recognise the emotion without being crippled by it.

In life, these aren't just themes, they're terrains — and the earthly stories that walk us through them, that give hope and lift us out of the mundane blindness with which we stumble miserably through those parts of the day we can't escape from, are the best works. They let us see the car-off-a-cliff for what it really is. Not spectacle, not "cool"... but grimly tragic. A story that can reach us and lift us from those places has value we can't measure on the bestseller list.

At some point, writers owe it to themselves to engage with the mucky, unpleasant, hard graphics of human existence. Places we don't want to go, but where we should go... for it's within those crucibles that our writing is forged into something stronger, deeper and more meaningful. And so, too, are we. It is our natural impulse not to look at the darkness. To shield our eyes. Yet writers have a unique opportunity, more so than other artistic forms, to address this darkness and find light there. It is the truth we lift from that darkness in our narrative. It is this that changes what we do from a craft to a calling.